É da Sua Natureza

In the summer, between noon and 3 p.m., go to Paineiras in the Tijuca Forest, step under the last waterfall in the Corcovado-Alto da Boa Vista direction, stretch your arms above your head and turn the palms of your hands upwards against the shower and observe the rainbow that forms on the circle of water around your body.

Marcos Chaves

It’s in your nature

“Humor opens up new paths”

Marcos Chaves

Effectively, Marcos Chaves started his production in the Eighties. And, even though he took part in the exhibition “Como vai você Geração 80?” [How Are You 80’s Generation?], his work and position were not at that moment associated with the international return-to-painting movement. On the contrary, they brought together renewed actions that retraced the trajectory from Duchamp to Neoconcretism1. The direct evocations of the Duchampian gesture clearly marked out the tradition to which his works alluded. Of course the ready-made as a proposition interested him. However, the appropriation of objects and their re-articulation promoted a different and unexpected experience. Taking an object and re-presenting it was to exhibit a profound drama with layers of meaning and implications of a cultural and social order. His attitude, like those of other artists of his generation can be linked with the conceptualism championed by many theoreticians when referring to the contemporary artistic output.

The artist’s assertion is significant: “There is already a lot of stuff in the world, I prefer recycling what is available”. This applies to the artist as an object maker and, above all, to the notion of objects of art magnetized with content in themselves, independent from interpersonal relationships with the subject. And yet, if on the one hand the excesses of a consumerist society afflict him – in which case his relationship with whatever is produced is surely a form of criticism – on the other hand, he is left with the challenge of transforming each given object into another being. And it is precisely this “new being” of the object that establishes his poetics. In this sense, the notion of ready-made, as an element removed from a specific context and highlighted in another, practically disappears. His objects create a new system of relationships and are given back to us in their transsignificant dynamics. It is the world made up of animated and non-animated things: furniture, ornaments, clothing, language, sound, etc. Even the medium employed to create the work is an object, whether it is a drawing, a video or a photograph. The object is the medium, and the medium is also an object.

What Marcos Chaves does is to give essence to things without destroying their original function. He lends them meanings, which pertain and are pertinent to them. For example, the artist takes a pair of high-heeled red shoes worn by a transvestite and positions them so as to form a heart shape and the shape of Fallopian tubes, alluding to successive layers of the feminine universe: Eros, the body, motherhood… All aspects of femininity are directed towards the will of a member of the male sex who aspires for the feminine sex. This is a piece that emphasizes the sense of “transitions”, rather than extremes, and which is an axis of resonances. For, even though at first it is taken as a privately owned object, it is presented with its collective implications. The object in its strict sense is of no interest because it would be particularly connected to a certain peculiarity, which would restrict the scope of discussions around it. According to Nicolas Bourriaud, one of the fundamental characteristics of contemporary art from the 90’s, and which I regard as a noticeable position of today’s artistic output: “…the relative immateriality of the art of the ‘90s — a sign that its artists grant priority to time, more than to space or to the wish to reproduce objects — is not motivated by an esthetic militancy or by a manneristic refusal to create objects. The artists exhibit and explore the process that leads to the objects, to the meaning.”2 His objects — which appear in connection with their function in society — self-articulate themselves in a significant mesh capable of a feedback of ideas deriving from the way in which the former are unexpectedly rearticulated.

Turning one thing into another without touching its physical structure or noticing a surprising element produced by someone else is one of the characteristics that punctuate his work. We can ask ourselves, “how does one promote the transitions between two things?”, or even “how does one impart it with meaning?”, or indeed “How does one turn something into something else without making the original disappear?” Maybe the question goes a bit deeper, because the nature of things in their full function is to be only what they have been built for or what they conventionally exist for. The principle of this work is the non-existence of something followed by something else: a before and an after for the apprehended object. What will be returned it is precisely the universe from which it was discarded, so that this dynamics can be noticed. Or, more accurately, noticed as a situation made up of transitions: here and there, side by side, simultaneously — stemming from the notion that apparently incongruent things can adjust and readjust to each other. In the video titled Laughing Mask, the apparent disconnection between tragedy and comedy gives place to oscillations between tragedy and comedy, which presents them as analogous entities — to the extent that laughter is swallowed up by pain and this pain restores the vanished laughter. The mask that laughs is the same that cries, as though to remind us that tragedy (from the dithyrambs) and comedy (from the phallic songs) have the same Dionysian origin, as well as it is Dionysian the impulse which gives momentum to this work. This way, the artist helps us put things side by side with instantaneous transitions free from attrition. For the artist, comedy and tragedy articulate each other, shuttling back and forth. There is not an outside space and an inside space, or a space inbetween, or indeed tension between opposite poles. No. Actually, there are transitions, variations, interconnected trajectories. This procedure alludes to the paraconscious logic of philosopher Newton da Costa, who predicts, as he himself puts it, the solution for “contradictory situations and opinions”3. By rearticulating things, the artist promotes transitions. And transitions are challenges. To articulate is to rearticulate reality. In this sense, we participate in the objectual articulations as we are faced with it.

Marcos Chaves developed a photographic series called Agreements (Acordos), which shows nature’s dialogue and adaptation in relation to iron and concrete structures, such as fences, gates, walls etc. An agreement is a way of proceeding with the aim of making coexistence possible. What the artist presents us with is the possibility of finding ourselves more prone towards our own malleability, what actually seems to be our body’s natural inclination. Agreements between differences are proposed as an effort to stay together sharing the same territory, since politics has failed in its role of coordinating life.

The work points to advantageous procedures, authentically correct to the detriment of political correctness. This applies to everything that can offend or limit the liberty which the other is entitled to. The series More than enough room (Lugar de sobra) — small stools built by the population with surplus of recycled materials — emphasizes the fact that each individual can give up consumerism in favor of constructing something creatively. This corresponds to the artistic maxim “take part” or “do it yourself”, which is a way of responding to collectivity and its individualities, starting from ourselves. No two things are identical. The whole is made up of differences. This position in relation to the subject evokes the propositions in the Brazilian experience originating from Neoconcretism and Tropicalism of such artists as Hélio Oiticica with his Parangolés, Lygia Clark with her Relational Objects (Objetos relacionais), and Lygia Pape — Marcos Chaves studied under the latter — in Wheel of Pleasures (Roda dos prazeres). The experience of sharing and interacting which the artist proposes is in part an unfoldment of exclusively Brazilian artistic movements.

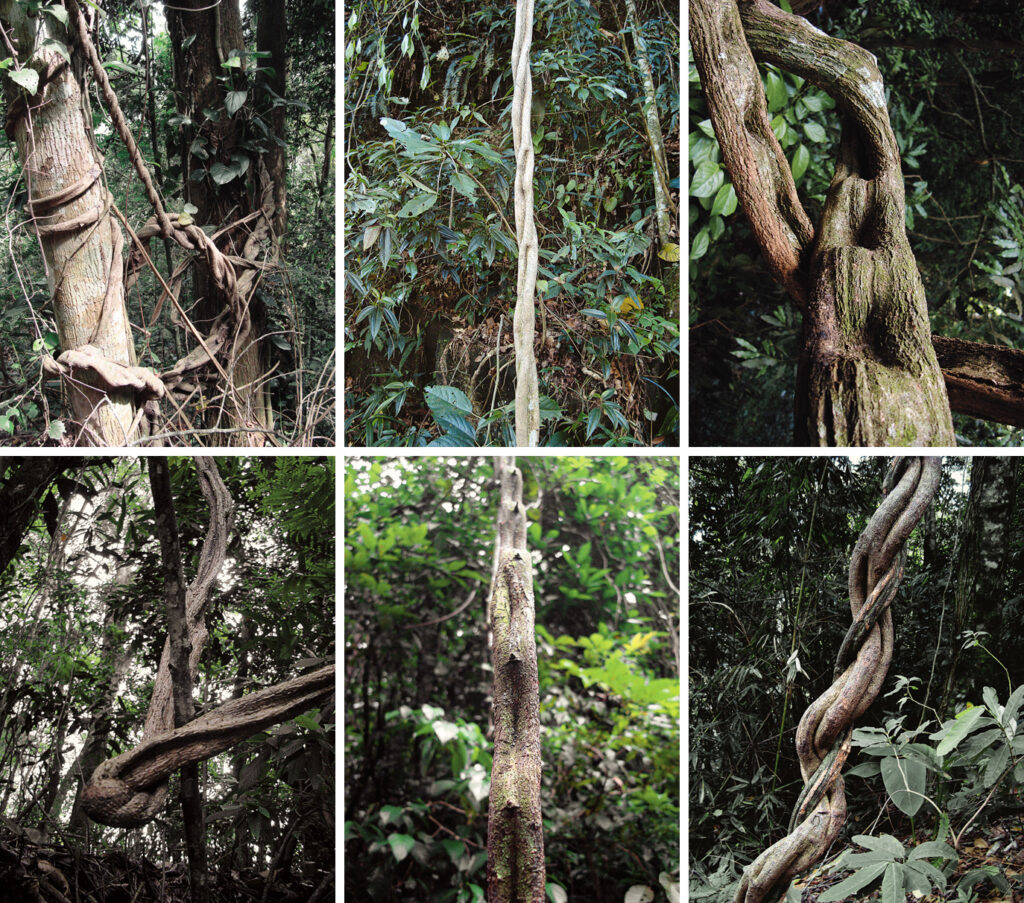

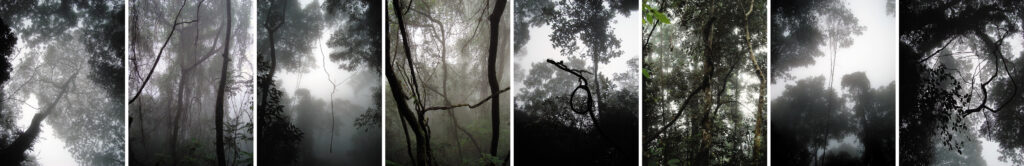

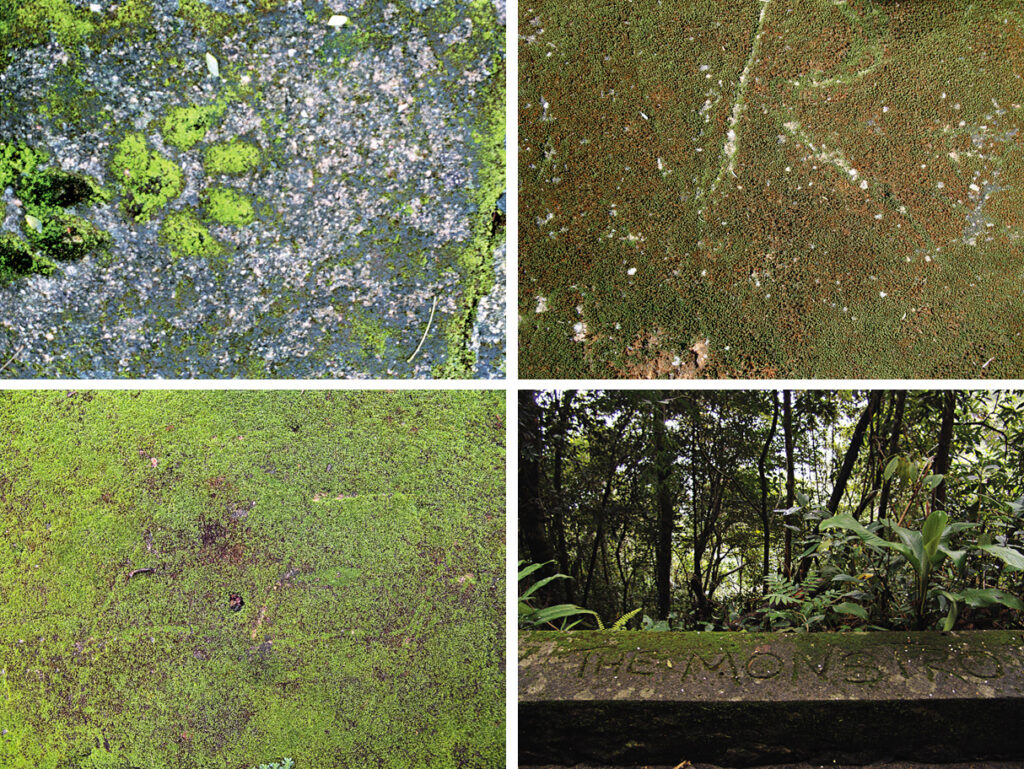

Perhaps the neuralgic point of his work is the relationship between Nature and Culture. But every artifice is ultimately subject to the natural order of the world. Therefore, it is necessary to discuss them conjointly. The artist appropriates the yellow and black tape of urban signaling and applies it to the most varied urban situations. The tape is brought up to its maximum potential in the work Public Area (Logradouro), in which its pattern establishes a place where the experience of the artificial world is realized as visual vibration and virtual space. However, the word “logradouro” has in it, in Portuguese, the word “gold” (ouro), as if to indicate that there is as much gold in the act of signaling as in this new place. This is nothing short of an exacerbated noise, but it is also harmonizing, because on the opposite side of the public area is the series Us — Tijuca Forest (Nós — Floresta da Tijuca) — with the suggested double entendre in Portuguese, linking the knots of the lianas with the personal pronoun (first person plural: nós = us), as if to insert us into the landscape, into nature in its pure, raw state. Even though Public Area and Us appear to be incongruent works, this is not really the case, given that, as we have seen, the poetics of the artist is constituted by the proposition implied in the agreements between nature and artifice (culture). The series Mutation (Mutação), in which the artist camouflages the leaves of forests with the yellow and black tape, proves this. He is interested both in nature and culture, and his work tends to articulate these signs so that artificial and natural processes merge — until the metaphorical sense of “mutation” is achieved, being this the way nature absorbs the signaling patterns of the urban center.

Flaws, noises (visual and sonic), fissures, sediments, accommodations, imperfections, deformations and all variations of what is recognized as an “error” that can escape social pre-determination are of great interest to the artist. What is on the laterality or that which is subjacent form the material he employs in the making of his “uncertainties” and “possibilities”.

His artistic productions work as an illuminating signal of things, something which doesn’t let us forget that “imperfections” exist, and that maybe we should take advantage of them, precisely because what seems imperfect and defective to us is merely an aspect of the way in which we build our culture.

In The Laughing Container — a container placed on a public square from where resonates the sound of laughter produced intermittently by a group of people — points to what Nicolas Bourriaud calls “relational esthetics”, i.e. “like the geometric place of a negotiation between numerous senders and addresses” 4.

If, on the one hand, it is laughter placed on a public square, on the other hand it is the ironic contention of laughter. According to Bergson, “our laughter is always the laughter of a group”.5 And also, “it is the business of laughter to repress any separatist tendency. Its role is to correct rigidity, transforming it into plasticity, is to readapt the individual to the whole, in short, to round off the hard edges”.6

For the artist, “irony and humor make it possible to talk about something with concision and to say many things at the same time. Humor opens up new paths”. Humor, irony and ambiguity are resources used to destabilize bureaucracy and seriousness. Of course, it creates some discomfort, but it is also the main tool or device employed in the process of integration and amalgamation with the participating subject.

The artist wittily employs puns and word games. For Bergson, “in every witty man there is something of a poet”7 and, also, “in a pun, the same phrase appears to offer two independent meanings, but this is no more than appearance, for, in reality, there are two different phrases, which we pretend to mistake for one another, taking advantage of the fact that they sound identical to our ears.”8 And, indeed, in this exercise of image and text which Marcos Chaves proposes lies the nature of poetry: that of a visual poet.

His witty puns create a “vacuum” where there are absolute certainties and defined truths. For this reason, the text (puns) is always salient in his work, so that different experiences can be brought to life, taking into account the fact that society’s status is based on survival. The experience of life presupposes the cooling down of the body. His procedure with the text reminds us of the eastern Buddhist system of the use of language, question and answer, in the process of de-conditioning the individual: the Koan.

Finally, we can ask: where does this work take us? One answer would be that the result of this complex game of interchange in the end promotes the union with the myth. In reality, we make use of mythological experiences, because in some way the myth is presented as an absolute value and we resort to it as an everyday fact. Man is himself an object in a tangential course through irrational meanders which allow him to integrate with nature effectively? Perhaps… as part of active mythical panoramic views. As summarized by his work The Pot (O Pote) — which works as a manual of instructions — in which the Irish fable of the rainbow is rearticulated as a real experience. The rainbow and the pot of gold are ultimately latencies in the articulations with life. Let’s see:

In the summer, between noon and 3 p.m., go to Paineiras in the Tijuca Forest, step under the last waterfall in the Corcovado-Alto da Boa Vista direction, stretch your arms above your head and turn the palms of your hands upwards against the shower and observe the rainbow that forms on the circle of water around your body.

Marcos Chaves

Alberto Saraiva

Rio de Janeiro, September 2008.

Endnotes

1 Neoconcretism: Artistic movement that emerged in Rio de Janeiro in the late 1950s as a reaction to orthodox concretism. The neoconcretists searched for new paths declaring that art is not a mere object: it possesses sensitivity, expressiveness, subjectivity, going far beyond the mere, pure geometrism. They were

against the science-oriented and positivistic attitudes in art. The recuperation of the creative possiblities of the artist and the effective incorporation of the observer are presented as attempts to eliminate the techno-scientific trend exisiting in concretism.

2 Bourriaud, Nicolas. Estética Relacional [Relational Esthetics]. 1st edition. Buenos Aires: Adriana Hidalgo Editora, 2006, p. 144 e p. 65.

3 Interview: Newton da Costa: June 2008. http://revistapesquisa.fapesp.br.

4 Bourriaud, Nicolas, op. cit, p. 29.

5 Bergson, Henri. O Riso. 2nd edition. São Paulo: Martins Fontes, 2007, p. 5.

6 Idem, p. 132.

7 Ibidem, p. 78.

8 Ibidem, p. 90.