Let's have a date in Saara?

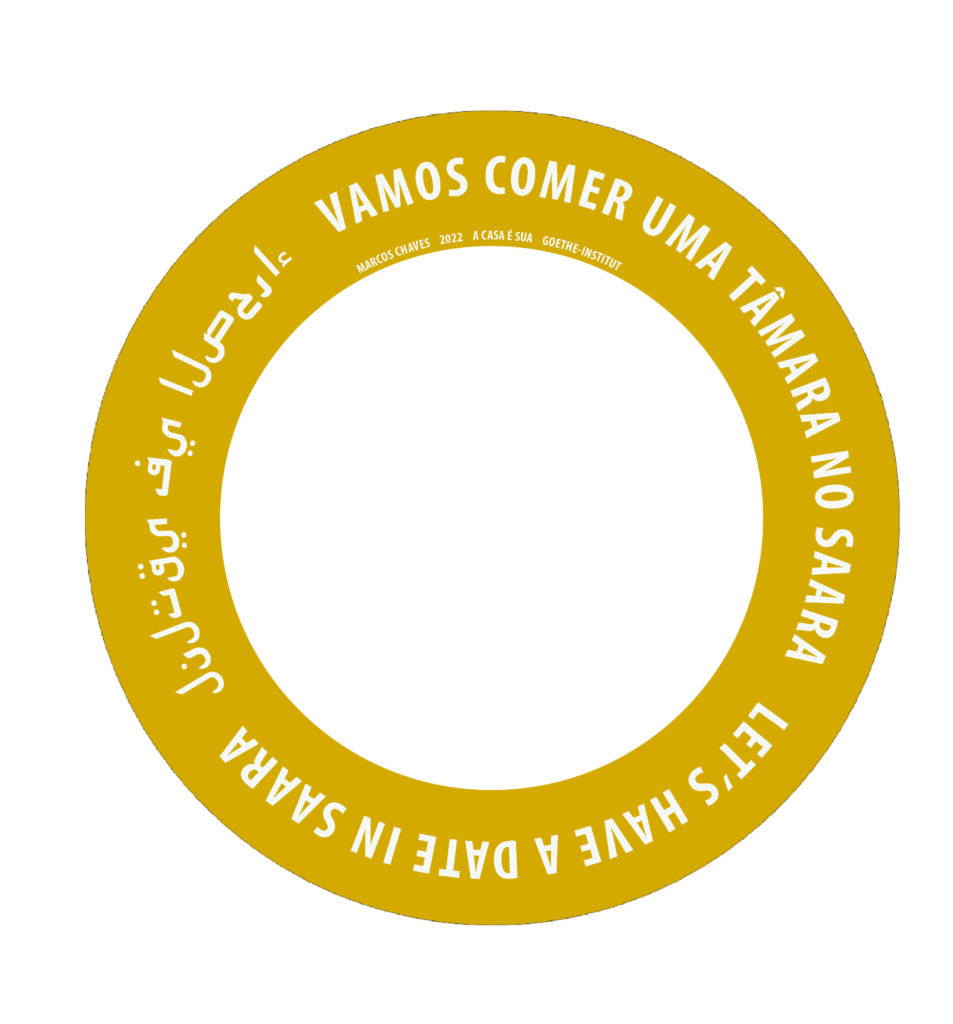

Commissioned for the exhibition “The house is yours: migration and out-of-place hos(ti)pitality” (Paço Imperial, Rio de Janeiro), Marcos Chaves’ public art intervention consisted of planting a “migrant” date palm in the only triangle-shaped square in SAARA (an acronym for Sociedade de Amigos das Adjacências da Rua da Alfândega, which translates to “Society of Friends of the Surroundings of Alfândega street”), an area of Rio de Janeiro where many immigrants from the Middle East settled at the beginning of the 20th century. A strong symbol of generosity and fertility, this date palm will settle amongst already-existing local palm trees, turning the square into an area of hospitality, just as SAARA has grown to become an important retail hub where merchants from diverse backgrounds work side by side in tolerance and acceptance. Visually similar, the date palm and local palm trees have very different origins and properties. The date palm is a tree which grows in the oasis of deserts, considered sacred by all religions as mentioned in the Koran, the Bible, in Persian proverbs and depicted in Egyptian inscriptions. Before being genetically modified, the date palm used to take 80 to 90 years to bear fruit after being planted, giving it plenty of time to adapt to its new and alien environment. On the ground, around the trunk of the date palm, a plaque is installed inscribed with a sentence in Portuguese, English and Arabic. The three sentences craftily play on the words used in the different languages. In English, “Let’s have a date in SAARA?”, the word “date” refers to a social or romantic meeting, but phonetically can be mistaken for the fruit that the date palm bears, hence the translation to Portuguese “Vamos Comer Uma Tâmara no SAARA” which literally translates to “Let’s eat a date in SAARA”. However, whereas SAARA refers to the market in central Rio, it can be interpreted phonetically as the Sahara desert, hence the translation in Arabic to لنلتقي في الصحراء, which literally translates to “Let’s meet in the desert”. As rainwater drains through the hollow letters to irrigate the palm’s, the statements, with very different meanings in each language, humorously reflect typical mistakes which can be made by beginners in a foreign language.

In the same spirit of this public intervention and alongside it, Chaves also collaborated with Rádio SAARA on a public sound intervention, in which he invited the exhibition’s participating artists to submit phrases, proverbs or idioms in the language of their choice, such as “those who plant dates don’t harvest them, a saying which encourages actions beyond the self, as it takes date palm trees 80 to 90 years to bear fruit. These were compiled and broadcast in Portuguese on the radio through the streets of SAARA and for the length of the exhibition. Whereas phrases related to the date palm tree and its role in history, or proverbs related to hospitality and the similarities and dissonances between languages were requested, Chaves’ interest lay in the tension and provocation that some idioms can create.

Amanda Abi Khalil