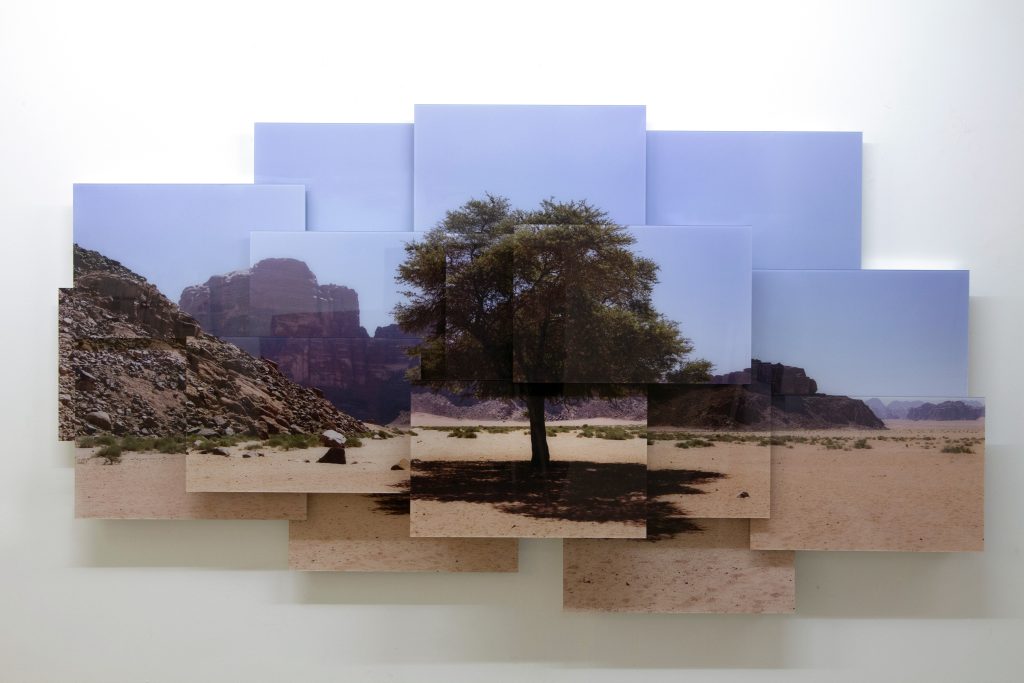

Justapostos

Uma paisagem é dissecada em vários planos distintos enquanto as perspectivas,

oscilantes, são reestruturadas num novo arranjo visual. Das imagens sobrepostas, como

que ativadas pela fricção dos encontros, elevam-se movimentos inusitados que evocam

e afastam, ao mesmo tempo, os primeiros estudos fotográficos que deram origem ao

cinema. Justapostos é um trabalho, sobretudo, de montagem. Uma montagem em duas

etapas e que tem início já no contato direto com os recortes do espaço definido. É o ato

fotográfico que destrincha a paisagem, fatiando o tempo e as ações em andamento. Na

sequência, a montagem prossegue com as imagens em mãos e é onde os planos se

embaralham. À medida que o trabalho vai ganhando corpo e deixando as perspectivas

clássicas renascentistas de lado, as durações estabelecem novos relevos, outros

encaixes temporais, não-lineares, transcorrem. Esculpe-se o tempo, como diria Andrei

Tarkovsky sobre o fazer cinematográfico. Nos primeiros trabalhos da série, Marcos

Chaves imprimiu as imagens em metacrilato, uma técnica que permite criar um efeito de

profundidade por conta da espessura do acrílico transparente, o suporte da impressão.

Todo esse peso, entretanto, somadas as várias imagens, demanda uma estrutura firme

para que o trabalho seja montado com segurança. E essa estrutura reforçada, conforme

distribui as imagens nos planos, deixa áreas livres nas laterais, posteriormente

preenchidas com espelhos. Espelhos planos, como se sabe, não apenas refletem a luz

do ambiente como virtualizam (e invertem) a imagem criada, dando a impressão de

estender tudo o que está no seu raio de alcance. Assim, os espelhos laterais operam em

duas frentes: ajudam a distribuir a luz na composição geral e amplificam o zigue-zague

entre o real e o virtual. Os novos trabalhos da série, executados em meados de 2022,

contam com outro padrão de montagem. As fotografias são impressas em chapas de

alumínio composto, mais finas, e montadas sobre uma estrutura leve que encurta

consideravelmente os vãos entre os planos. A proximidade maior entre eles produz um

volume mais homogêneo, compactado, aumentando a sensação de estranheza do que

supomos ver – um desencaixe que, em realidade, agrega. Sem assumir um ponto central,

mas centralidades, a paisagem não cessa de se ramificar.

Yan Braz

Marcos Chaves’ Pieces

Cinelândia

From the terrace of Praça Floriano’s Café Cine Odeon a remarkable Brazilian panorama emerges. Beaux Arts exuberance of the late Empire sits alongside the rational Paulista exhilaration of the 1950s boom. The early century calçada mosaic pavement unmistakably recalls antique Roman Lusitania. While across Praça Mahatma Ghandi, a line of palm trees bend slightly in the breeze, calling to mind the endless Bahian coast and the cruel old Capitans’ feudal ambitions. Behind this crown of palms hovers the elegant curve of Brazil’s monument to its dead of the Second World War. A structure that proclaims the concrete modernism so wholeheartedly experienced in this place. The specters of Brazil’s many pasts somehow shimmer alongside one another in the air. It is as though Southern time, experienced here, is not running forward according to the Northern convention but instead is spiraling deeply inwards and embracing itself.

Naturally, at Café Cine Odeon we drink coffee.

Korea Town

I first encounter Marcos Chaves in a noisy Korean barbeque in Wang Jing—Beijing’s new satellite megacity. Chinese-Brazilian curator Sarina Tang has invited Chaves to make new works as part of an important exchange of artistic experiences between Brazil and China, and she has kindly arranged that I meet him.

I respond immediately to Chaves’ gently subversive performative interventions which are so full of intelligence and humor; these readymade sculptural juxtapositions relate so directly to the overwhelming visual experience of my Chinese city. For all the speciousness of comparisons between China and Brazil, one thing that they do have in common is a native genius for the accidental and the improvised. Indeed China abounds in startling surrealistic assemblages of mismatched daily items furnishing the street: a dirty, long-haired, pink mop dripping from a nail in a tree; a broken sofa; an abandoned board is a handy card table; the kiosk man’s roadside coal burner rustles up some lunch. These perfect Chinese situationist moments of sculpture were more than worthy of Chaves’ own Carioca observational zeal [“Carioca” refers to people born in Rio de Janeiro, TN].

São Paulo

Chaves took advantage of his Beijing residency time to create Pieces for Galeria Nara Roesler. In discussion with Chaves, it became clear that these works are not only a significant formal departure in his work but also reveal a deeper level of intimacy with which the artist is showing himself to the world. The work is the result of three years’ research and includes five large-scale, multiperspectival photographic panels. In these ambitious works the artist seems to take a mental journey, or reprise, of his own. In Ipanema he starts out close to home with a view from the Tijuca forest of the beach and beyond. He then takes a voyage which focuses nature in the city. Jardim exótico is the French medieval town of Eze, and Ficus macrophylla, the Botanical Gardens of Palermo, Sicily. Chaves returns at the end of the day to the home he missed so much with Prego, an inscrutable monkey from Santa Teresa shifting in the twilight.

In a formal sense these works relate, as with much of Chaves’ work, to the dynamics of placing elements in space. Here reverse perspectives take the foreground to the distance and bring distant objects to the fore. Their multiple viewpoints invite us to shift our visual stance and create narratives of our own: the monkey shuffles from branch to branch; the light on the horizon shifts; the single island becomes a fictitious personal archipelago, wistful perhaps, and full of possibilities. While much of Chaves’ previous work is concerned with creating new meanings in otherwise discarded moments of time, crucially, these works present conscious occasions in which the artist, although not personally visible, is fully present as a contemplative protagonist.

Chaves’ previous work has predominantly been lens based but for him the actual photograph is an almost incidental by-product in an otherwise intangible work. Here, however, the photographic image has decisively become a sophisticated object in its own right. The multiple viewpoints of the large panels are constructed with mirrors between their margins causing them, as author of the images, to reflect reflexively and endlessly back on themselves. Paradoxically, in revealing a more personal and ephemeral part of himself, the artist has, despite a practice that eschews materiality, produced his most physically substantial objects to date.

Santa Teresa & Chaoyang District

As I discover in Cinelândia, the way that Brazil’s unique and intense histories are so palpably available in the present allow them to somehow illuminate the narrative of Western culture with unusual clarity. Even the elegance of its formal counterpoise to Northern hegemonies confirms the extent to which we in the Western world form a large and diverse cultural sphere. My encounter with the work of Marcos Chaves functioned in precisely this way; through his works the radical logic of one hundred years of aesthetic philosophy fell coherently into place.

What unidentified feature caused this to take place, I wondered?

Santa Teresa, Chaoyang District & Lusitana

In 1990, Portuguese choreographer Madalena Victorino made an important dance work, TORREFAÇÃO, in Lisbon’s now defunct coffee mill Torrefação Lusitana. One veteran coffee worker from the mill, on seeing how the dancers melded their bodies with the dusty, coffee-impregnated floors, walls, and Hessian sacks commented to performer Gil Mendo, plainly, “entrega-te ao café”: you give yourself to the coffee. Over the past twenty years, I have returned repeatedly to that remark, and it has come to encapsulate for me a cultural and aesthetic practice that I suspect to be more central to Marcos Chaves’ work than has been previously explored.

This practice of giving oneself over is far from being an artistic posture of emotional enthusiasm. It is more crucially a subtle and disciplined response, which combines sophistication and empathy in equal measure. Over those years too I began to suspect that this practice may represent a particularly Lusophonic sensibility. A sensibility which I strongly detect in the works presented here. Chaves is considered a most Carioca of artists and, for all the intelligence of the syntax of his artistic production, it is fundamentally this practice of giving oneself over that transforms his works into quiet, compelling enigmas.

The video work presented here, A árvore que caminha (The tree that walks), shows a giant banyan-like tree in Campo de Santana, Rio de Janeiro. The tree’s aerial roots hang down in an impressive curtain over the pathway below. With a characteristic observational humor, Chaves captures the impulse of some passersby: to reach up and strike the fibrous tentacles.

They are giving themselves to the tree.

Simon Kirby

North South Lake, Zhejiang, China. October 2011