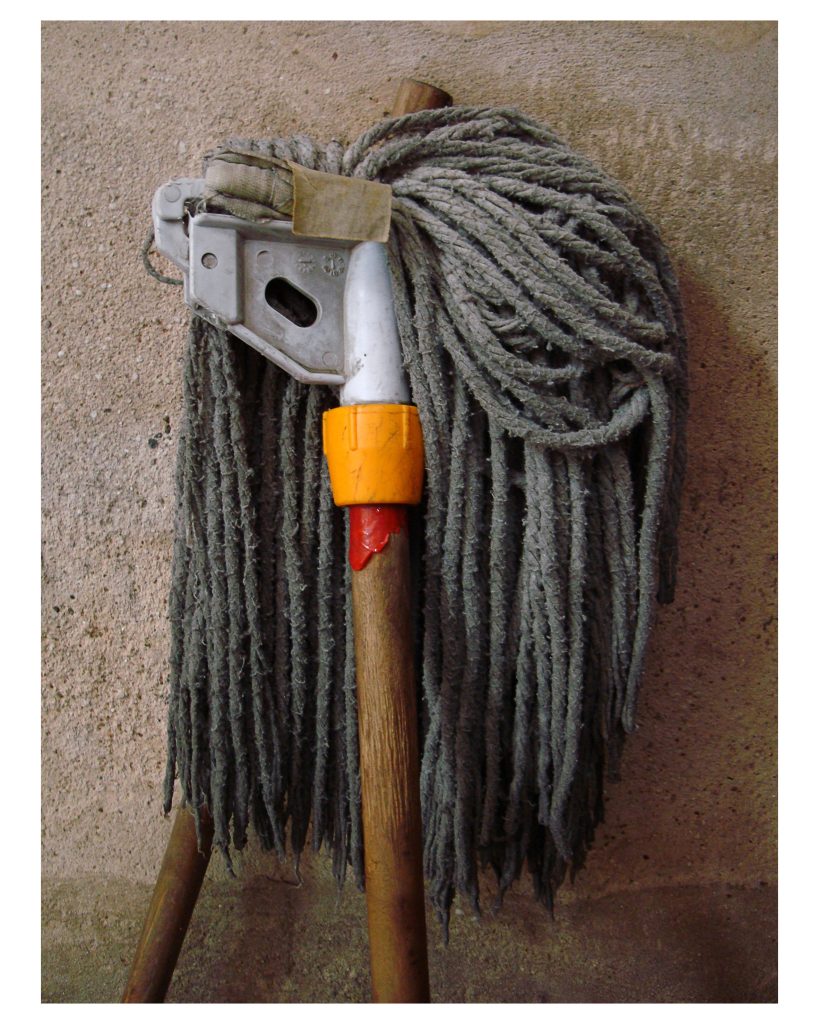

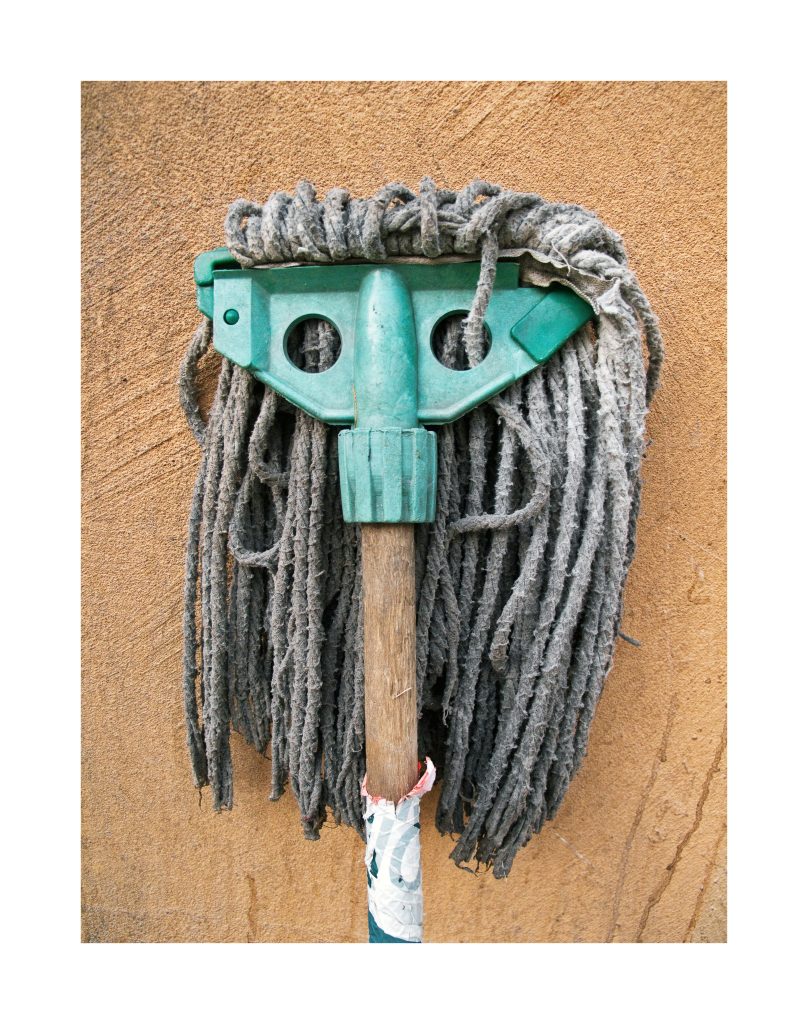

Portraits

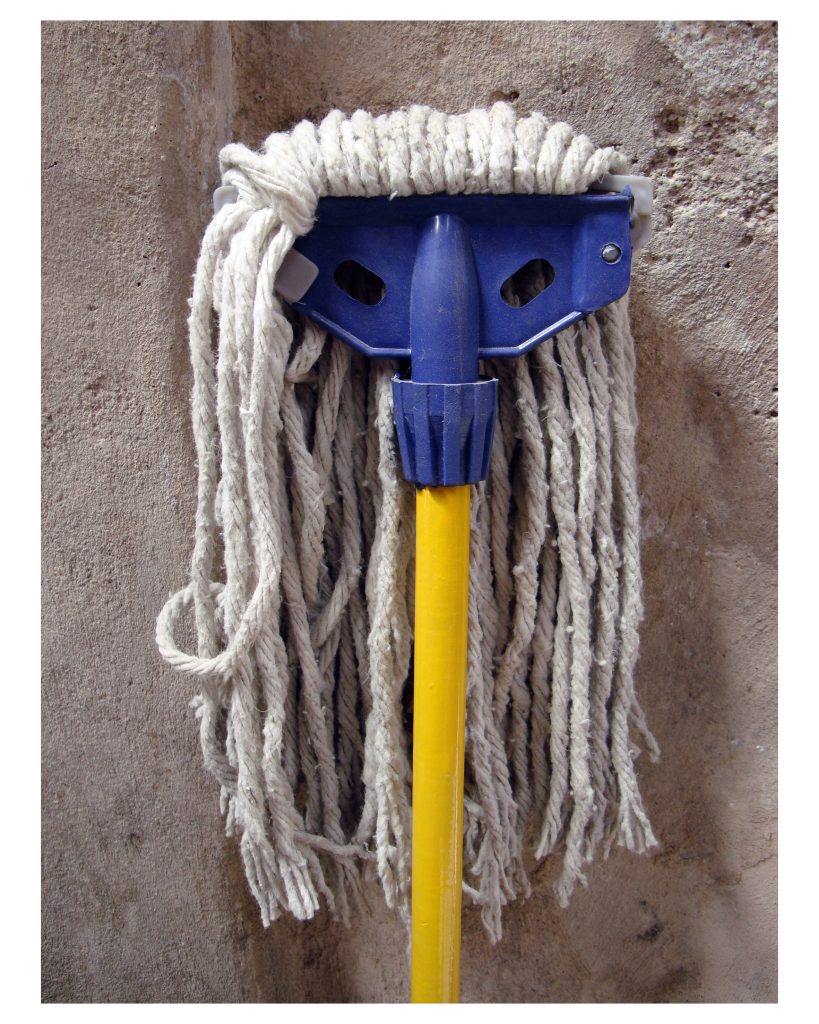

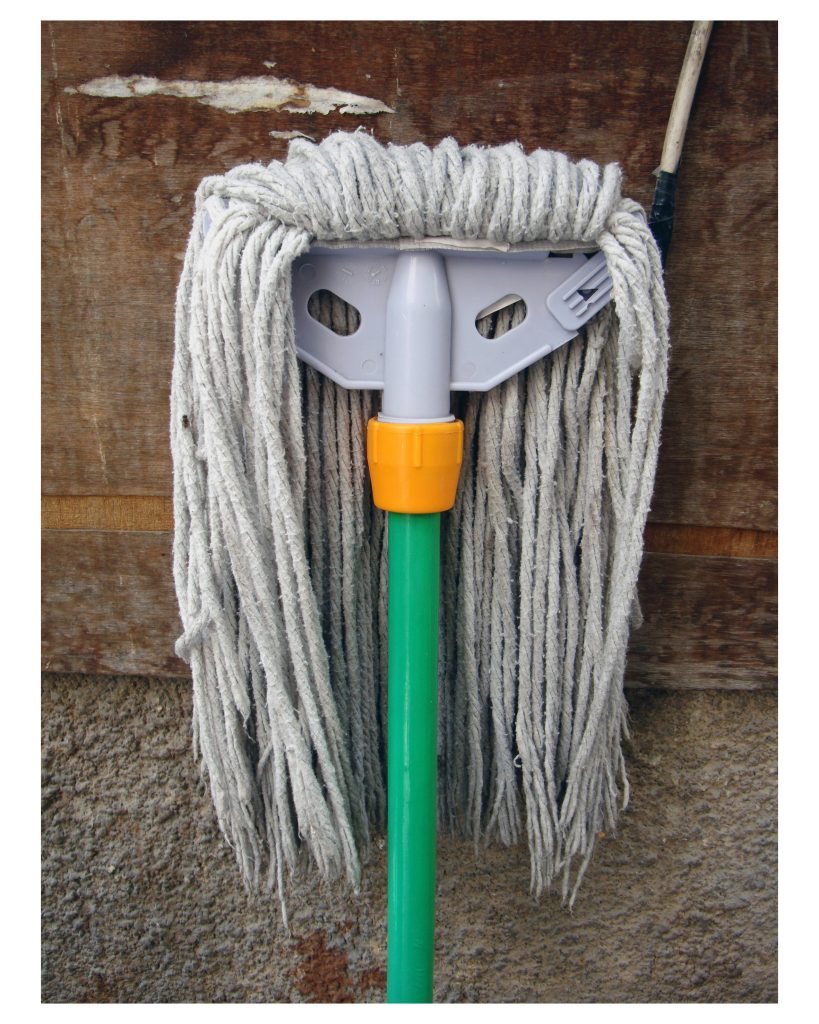

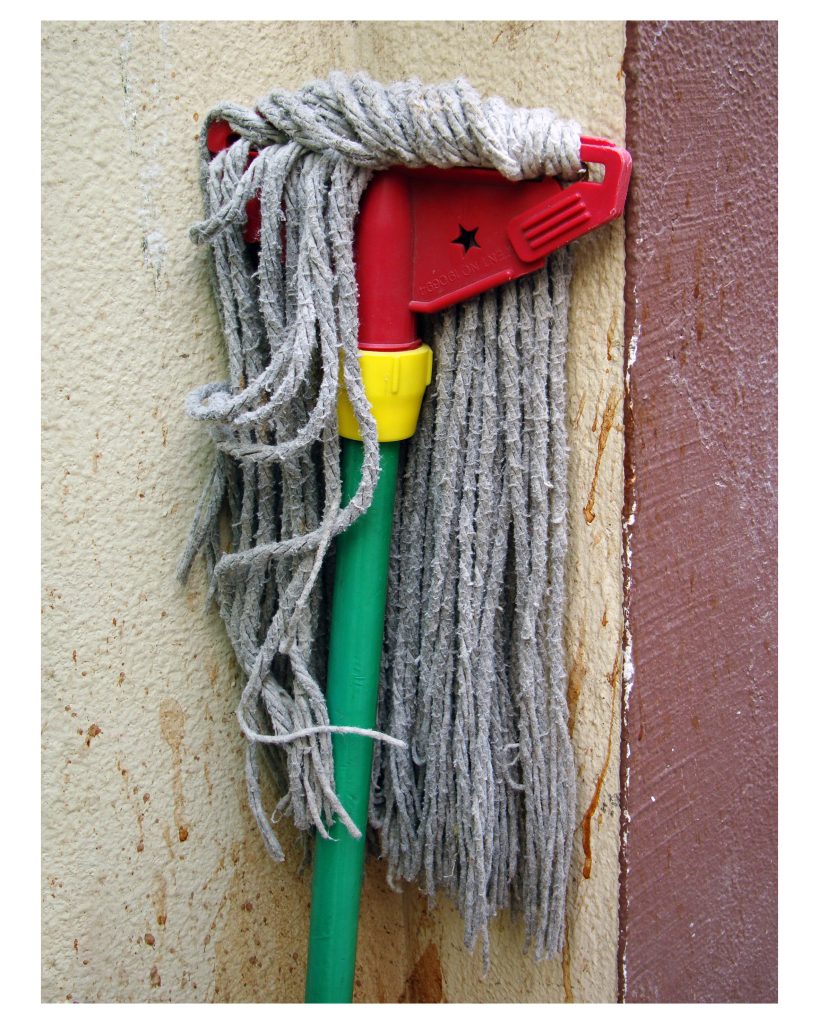

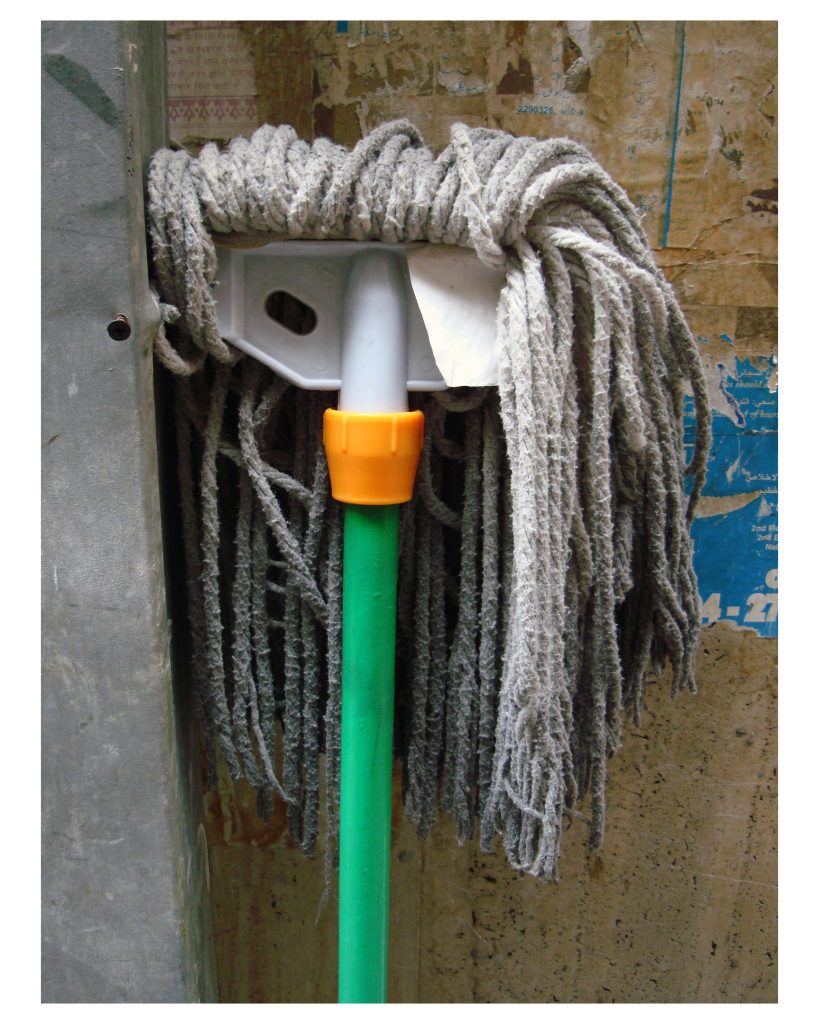

Marcos Chaves is a regular at antiques fairs and popular markets. His practice, not surprisingly, is permeated with objects bought in these places since the 1990s. When he visited Dubai, the most populous city in the United Arab Emirates Emirates, he visited one of these markets, locally known as a souk. But there, instead of buying objects, a habit of the traders caught his attention and received a longer look. Given its desert location, the frequent sandstorms require incessant cleaning of the market’s sidewalks and roads. After the routine cleaning, done with mops, a type of broom with absorbent fabric bristles with long, soft, absorbent fabric bristles, Chaves noticed a custom shared by shopkeepers by shopkeepers: turning the mop upside down, i.e. with the bristles facing upwards, so that it would dry upwards, so that they could dry, next to the stores.

These observations resulted in Portraits, a photographic series that projects an unexpected individuality of these cleaning tools through the typology developed by the artist. In this series, by dialog with the tradition of portraits in photography, which in turn comes from painting, the artist a perceptive commentary on the act of portraiture and its political implications in the social fabric. in the social fabric. After all, who was (is) portrayed? There is humor, of course, if we consider that a portrait, in order to be successful, must arouse empathy. If there is empathy, then there is recognition. We project ourselves onto what we we see. Knowing this, Marcos Chaves turns to pareidolia, a psychological phenomenon that makes our brains perceive recognizable meanings or patterns where they don’t actually exist. We thus glimpse some expressiveness embedded in the structure of the mops, while their long, soft bristles, like hair, give them organicity. Also unique are the textures present in the backgrounds on which the rest the portraits. From plywood to marble, the varied surfaces give the dimension of the frequency of use of the object, which have a certain similarity to each other, as if they came from the same place, or factory, and also show nuances of the economic life of a economic life of a popular market in one of the richest cities in the world.

Yan Braz

“Portraits” is not an exhibition of photographs of human faces. It presents 25 pictures of mops, which are used to clean floors. Upside down, with their yarns falling over the handle, they resemble faces: the yarns look like hair on the shoulders, and the vacant structure attached to the handle looks like eyes. The simple game of similarity is edgy. Each of these cleaning tools, all of them from the same species, has a personality, a haircut, etc. There is a visual joke, an irreverent image, like the mustache Duchamp put on the Monalisa’s picture.

These photographs, like other Chaves’ artworks, are like objet trouvé, found objects picked as art, but in this case, because they have been photographed, would be better to call them image trouvé. During an incursion through Dubai’s popular market, a sort of genuine SAARA, in the richest city of the Emirates, Marcos Chaves observed the mops that are left leaning on the walls, next to the stores, upside down, drying after being used to clean the sidewalks. The Arabs call them, in English, “brooms”. In Brazil, “vassouras”. In Portugal, “esfregona”, a feminine word, very adequate to the object in the context of this exhibition. The mops together become a “parade” of masks, but not like the African ones, primitive, nor Arabians, with veils. Their image does not intent to illustrate an exotic reality. In a multicultural world, these portraits deconstruct with humor a very stereotyped vision of another culture. These are not posed portraits, but instant snapshots. Instead of ethnology of the Arabian world, the images reveal a thousand faces of the ordinary object.

The exhibition also presents three marquetry photo-frames with Arabian motif and images of the sun, constituting a typical desert landscape. The work unmasks representation, both in art and culture, with a calculated laugh very characteristic of Marcos Chaves’ artworks.

November 2009.

Fernando Gerheim