Holes

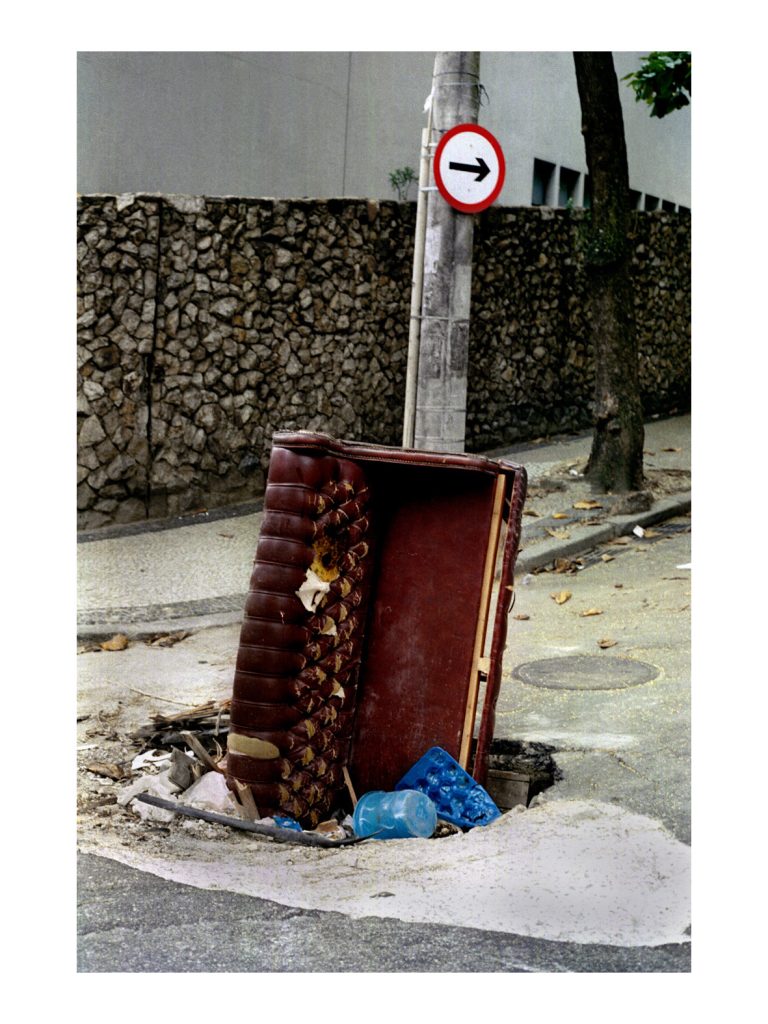

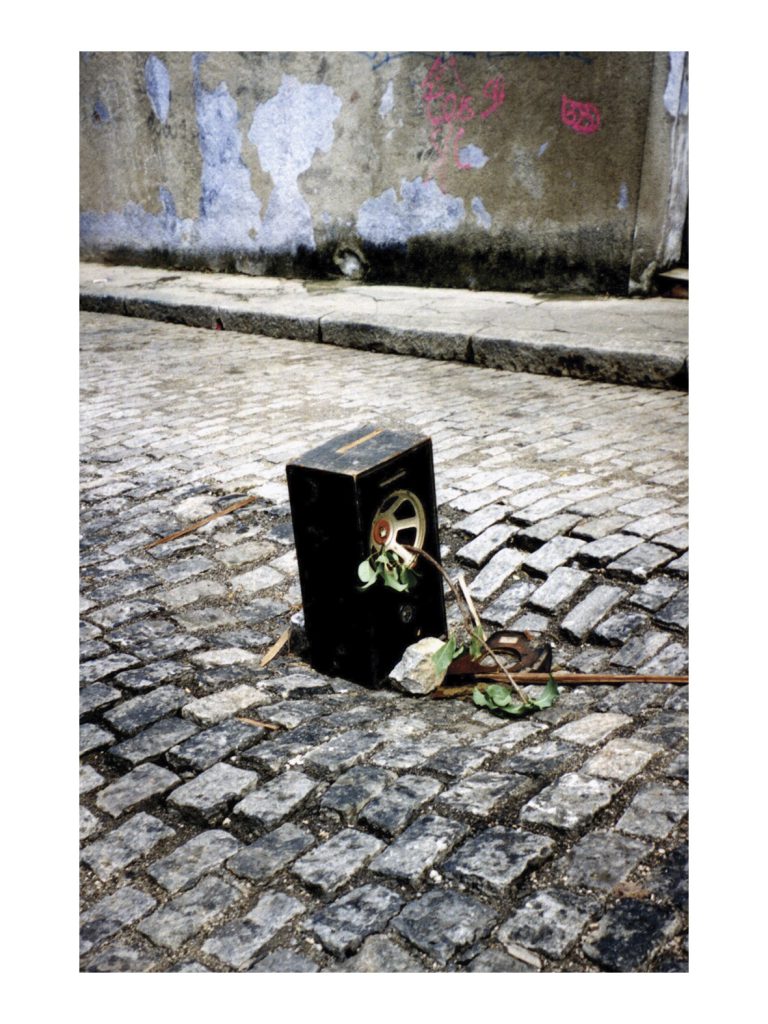

A long-term photographic series dedicated to organizing a typology of interventions made by anonymous people in potholes in the streets of the city of Rio de Janeiro, especially in the streets of Santa Teresa, the artist’s place of residence at the time the series began. Santa Teresa is a Rio neighborhood known, among other things, for its cable cars and for being connected to some of the city’s most visited tourist attractions, such as Christ the Redeemer, the Dona Marta Lookout and the Arcos da Lapa, as well as being very popular with tourists. The interventions in the potholes, if we take into account their primary function, serve to warn drivers that there are obstacles on the road. In this way, they try to anticipate the sight of a problem and give drivers more time to solve it, or rather, to get around it. However, when we look at their variations and subtleties, we see something new that was once scattered throughout the urban fabric: the myriad of plastic solutions, made by anonymous people, to the same problem.

Of the inside-out of a hole, or another frontier

Adolfo Montejo Navas

There are works that create their frontiers, or, better saying, make them converge, not eliminating but re-dimensioning them with – it goes without saying – no customhouse spirit. Especially within a context where the culturally correct borderline discourses of our time celebrates it in its commercial appearances. With the word hybrid usually comes a mystification at any cost of the term, of this condition, as if yet another item of globalization. In the case of Marcos Chaves’ series Buracos (Holes), this same paradox takes place, but in a critical, attentive, lucid way, for instead of knowing we are before a defined and codified thing, we are always on the move, in a reflection that is never fixed to a place, where the very ground of the frontiers move, in several of their meanings. Maybe because the series, already from its starting point, invite us to this, to share different points of view, displacements that change their strategies, conceptual operations already implicit in the chosen, worked on and transposed visual matter.

This very same borderline condition is also explained by the several converging limits, by the fact that the series Buracos (Holes) is at the same time several indistinct things: it is a collective sculpture, a public installation, a popular intervention, and also a conceptual appropriation, a urban ready-made, a photography and, last but not least, a political work, and not necessarily in this order, for here what matter is multiplication and not sum. Nevertheless, each hole in a Rio de Janeiro street raises not only a tri-dimensional warning for pedestrians and, specially, for street traffic, but registers as well an unquestionable improvisation that lays further beyond the horizon of arte povera or the Dadaist discourse, perhaps in its wildest trend.

Like true urban phantasmagoria, then, Marcos Chaves has been rescuing local street interventions in the fashion of Kurt Schwitters-like apparitions. For each hole is a liability in the city’s public power, a symbolic fissure that is opened, a popular homage to the dangers of faulting politics that the social imaginary represents as a fracture. Each hole is an intervention that plays with presences and absences (of ground, of emptiness, of structure, of signs) and that is read with an accomplice and sardonic irony. It is not the first time that the artist approaches the urban imaginary of his city with a transversal and humorous gaze, but this time the aesthetic itinerary is different. As one can sense, in the Rio de Janeiro cartography there is no territory unity, for it is alleatory, mundane, nomad. To the high sum of circumstances, we must add the juxtaposition of elements that contribute for the work and that should as well be part of Paul Virilio’s Accident Museum: accident, chance, traffic, collage, improvisation.

The other dimension explored by the artist is found in the play of language – echoing Magritte – established in the title, which is simple, and in which hole is an inside-out representation, and a representational iceberg, whose meanings reach beyond the visible space. Here, put in the style of colloquial Portuguese, “the hole is further down”10. Once again, verbal and imagetic images are crossed; draw their abyss. As Mel Bochner once said: “There is a large abyss between the space of the statement and the space of the objects”11. Ever more so when the object aims to have other goals, to leave its logos, and the statement reaches another discursive space, where they can’t fit comfortably or categorically. For instance, photography itself – increasingly used by Marcos Chaves as a support – carries this division, this oblique glance that allows raising suspicions about reality and its fiction, about the nature of image and its irony, about its codes. In this way, the poetics of this work is born from a rupture that is explored between the real word, the sculpture that modifies it and its photographic documentation. The photos of the holes are self-representations, in which object and idea couple in their raw material (the piece lifted in the street) and in its category of thought (the photographic and conceptual registration), but in order to arrive at perverse tautologies, which never stop incurring on several levels of understanding. There are other signs on the road. Thus in this collection of holes one can see much more than one thinks.

10 “O buraco é mais embaixo” (Translator’s note).

11 BOCHNER, Mel. Considerações em torno da reinstalação de A theory of sculpture. Rio de Janeiro: Centro de Arte Hélio Oiticica, 1999. p. 25.